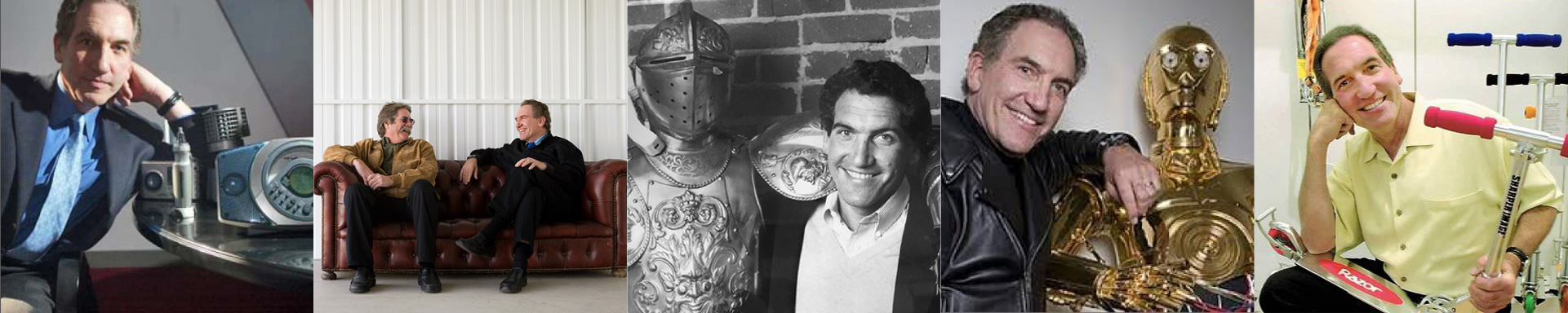

Richard Thalheimer, who collects vintage motorcycles, is the founder and CEO of Sharper Image. The retailer expects sales to rise by 20% this year. After staging a comeback the retailer’s founder takes aggressive steps to sustain momentum.

Matthew Kelley is a subscriber and fan of Consumer Reports magazine. But he also loves his Ionic Breeze room air cleaner from Sharper Image Corp.

So when Consumer Reports’ October issue termed the Ionic Breeze “ineffective” in cleaning the air, the Georgetown, Colo., accountant was torn. In the end, he sided with Sharper Image. In a letter to the magazine, he called the $300 product “a terrific purchase”.

“I rarely respond to things like this” in writing, Kelley, 33, said later. “But it’s made a difference in our home.”

Kelley’s loyalty is welcome news for Richard Thalheimer, Sharper Image’s founder, chairman, and chief executive. But Thalheimer is still livid over Consumer Reports’ assessment and has taken matters into his own hands. The retailer sued the magazine this month on grounds that its findings were false, misleading and harmful to the air cleaner’s sales and reputation.

“They pretend they’ve addressed our concerns, but they really haven’t, and we’re ticked,” Thalheimer said. Consumer Reports said it stood by its story as “truthful, fair and accurate.”

Companies seldom sue Consumer Reports, but Thalheimer took the aggressive step to help protect the brisk sales momentum enjoyed not only by the Ionic Breeze air cleaners but by Sharper Image overall.

Once a peddler of expensive and largely unnecessary gadgets to upper-income men, Sharper Image now sells a broader, more useful product line to men and women — and the company is on a roll.

Sales and earnings are up smartly, and the company’s stronger stock price and debt-free balance sheet are enabling Sharper Image to step up its store expansion.

Rising sales from the company’s catalog and Internet operations, which together account for about 40% of Sharper Image’s business, also are fueling growth. It’s all backed by nearly $100 million in annual advertising that includes lots of TV infomercials.

“This is not the boy-toy company of 20 years ago,” said Thalheimer (pronounced TALL- heimer). “Today our bestsellers are an air filter, an eyeglass cleaner, and a nose-hair trimmer.”

The company’s sales per square foot are running above $625 annually, “at the high end” of specialty retailers in general, said Kristine Koerber, an analyst with WR Hambrecht & Co., which has had an investment banking relationship with Sharper Image.

Through the first seven months of this year, the chain’s same-store sales — those of stores open at least 12 months, a key measure of retail success — jumped a stout 15% from a year earlier. Sharper Image expects its total sales to grow 20% this year, to about $635 million, and it’s gunning to reach $1 billion by 2006. Earnings also are forecast to rise about 20% to roughly $22 million, according to analysts surveyed by Thomson First Call.

The retailer, which once operated only in the toniest shopping malls, also has expanded into the heartland with stores in Fresno; Omaha; Peoria, Ill.; and Little Rock, Ark. And more are coming. Sharper Image, now with 130 stores — including 32 in California — plans to open 25 additional stores this year and 25 to 30 next year.

Even the weak economy and sagging consumer confidence aren’t impeding the company’s momentum. Credit not only the chain’s broader appeal and a wider range of prices but also its shift toward selling unique products under its own brand, analysts said.

For Sharper Image, it’s a strategy that Thalheimer, 55, began developing several years ago after he had to pull Sharper Image from the brink of disaster.

A Background in Retail

The son of Little Rock department store owners, Thalheimer graduated from Yale University, moved to San Francisco in the early 1970s and began selling copier and typewriter supplies to offices. That’s when he coined the name “The Sharper Image.”

Then an avid runner, he discovered a multifunctional watch he was sure runners would want, but the item had narrow distribution. After striking a deal with the watch’s producer, he ran a full-page ad in a running magazine, and the orders poured in.

He made a small fortune, which gave him the springboard to start selling other goods by 1977.

“I took all the money and put it into a color catalog, a computer, and an office,” he recalled. For its first 10 years, Sharper Image became synonymous with the trendy, often frivolous consumption of the 1980s. It sold mainly high-end consumer electronics made by Sony, Panasonic and other companies, and expensive toys such as suits of armor and crossbows. Its target shoppers were mean earning six figures or more.

Thalheimer took the company public in 1987 at $10 a share and then began to leave the daily operations to others. The go-go economy of the 1980s was ending, and a deep recession was around the corner. In addition, many Sharper Image products — stereos, TVs and telephones — were becoming available at electronics chains and mass merchandisers, whose price-cutting eroded Sharper Image’s popularity.

Sales plummeted. Nonetheless, Sharper Image continued to rapidly open new stores, swelling the company’s costs. The chain lost $2.3million in 1990, its first annual deficit, and its stock plunged to less than $2 a share. Thalheimer, who owned more than 70% of the stock at the time, saw his personal fortune nose-dive.

“We had to come up with a new business formula,” he said. Thalheimer went back to work. The solution, he decided, was to sell more exclusive products and to design many of those products in-house. He also set out to find a broader range of goods that included items at less than $50 and merchandise that would appeal to men and women. In addition, he slashed expenses until the company could recover.

Thalheimer spent much of the 1990s shifting Sharper Image’s focus, during which its sales rose only modestly and its stock price languished in the single digits. He concentrated on new-product design and merchandising. Tracy Wan, formerly Sharper Image’s chief financial officer and now its president, focused on running the business and its stores more efficiently.

The transformation began paying off three years ago on strong sales of the chain’s air purifiers, exotic DVD players, shower CD players and other items. The Sharper Image brand (along with other in-house brands such as Ionic Breeze) now accounts for 80% of sales.

Other bestsellers include a $79.95 “mini-fridge” for the car that keeps food cold or hot. There’s a $799.95 “personal entertainment center” that looks like a laptop computer from the outside but inside has a DVD player, CD player, TV, speakers, alarm clock and other doodads. A “talking pictures” photo album for $29.95 lets buyers record a 10- second message to accompany each photograph.

Thalheimer’s products illustrate that he’s “a futurist with a very strong sense of what people will buy,” said E. Robert Wallach, a friend of Thalheimer’s and San Francisco lawyer who’s handling Sharper Image’s lawsuit against Consumer Reports.

Sharper Image also reaps relatively high profit margins from its own brands. That’s because they’re not available elsewhere and aren’t subject to price-cutting by others, analysts said.

The company’s growth enabled Sharper Image and Thalheimer to sell an additional 2.5 million shares of stock to the public for $19.50 apiece in May. The stock has since climbed 26%, closing Friday at $24.57, down 32 cents, on Nasdaq.

That’s fortunate for Thalheimer, who still owns 24% of the firm or about 3.4 million shares valued at about $85 million. Thalheimer no longer runs but still swims each day and pilots his single-engine airplane to visit stores and clients. He collects and rides vintage motorcycles, five of which are displayed around Sharper Image’s headquarters here.

He still does much of Sharper Image’s buying from other manufacturers, while heading the design, advertising, and marketing of the company’s in-house gear. Sharper Image’s branded merchandise is built to its specifications by about 10 outside producers, mostly in China.

And despite his reputation as a personable, almost father-like CEO, he’s not hesitant to sue those he believes are trampling on Sharper Image’s business — including Consumer Reports.

Formidable Foe

The nonprofit magazine says it has not lost a libel or “product disparagement” lawsuit in the last 35 years, nor has it paid any damages to settle such cases.

The magazine actually called Sharper Image’s Ionic Breeze cleaners into question a year ago. Sharper Image complained that Consumer Reports was applying rigid testing formulas that didn’t take into account the product’s new technology.

But sales were unaffected, Thalheimer said, adding that Sharper Image had sold more than 1 million Ionic Breeze cleaners. “It was bad enough the first time, but nobody cared,” he said.

Then in its current issue, Consumer Reports tested the Ionic Breeze and other air cleaners anew. Once again, it found the Sharper Image device “ineffective.” So Sharper Image sued in U.S. District Court in San Francisco.

Consumer Reports said its first test “found almost no measurable reduction in airborne particles” from the Ionic Breeze, and the second test “has not changed our judgment.”

Sharper Image contends that Consumer Reports relies too heavily on a conventional measurement of a cleaner’s “clean- air delivery rate,” or CADR. That’s “an unfair and inappropriate measure” of the Ionic Breeze’s technology, the company said in its lawsuit.

“It’s like measuring a car based only on how fast it can go from zero to 60 miles per hour,” Thalheimer said. “There’s a whole new technology out there of silent air movement using electrostatic and ionic propulsion of air, and they’re ignoring it.”

In plain English, Sharper Image is arguing that Consumer Reports’ testing method is biased in favor of cleaners that use high-speed fans to rapidly move air through the cleaners. The fan-less and low-energy Ionic Breeze uses stainless-steel blades to trap pollutants and is designed to clean the air continuously while being left on over a long period.

Consumer Reports said that the second time, it ran a longer test of nearly 24 hours to compare the Ionic Breeze against rival cleaners, and the Ionic Breeze still “didn’t come close to the performance of the others.”

Sharper Image argues that the second test didn’t accurately account for how users of fan-based cleaners typically shut them off after a few hours, while Ionic Breeze users keep theirs on continuously.

Wallach, the lawyer, acknowledged that Consumer Reports has never lost a libel case because there is “a very high threshold that’s required to prove malice against a public entity” such as the magazine.

Even so, Consumer Reports used a testing procedure “that they knew was certain to produce what was a failure by their standards” with the Ionic Breeze —and that amounted to malice, Wallach maintained.

Consumer Reports responded that its test procedures “are valid.”

The latest article hasn’t dented sales of the Ionic Breeze cleaners, Thalheimer said. But Kelley, the accountant who wrote the letter, illustrates the danger Sharper Image still faces.

“I rely on Consumer Reports for a lot of my purchases,” Kelley said. “Is it possible I might not have bought the product after reading that? Yeah.”