SAN FRANCISCO —

Richard Thalheimer knows a thing or two about pride going before the fall.

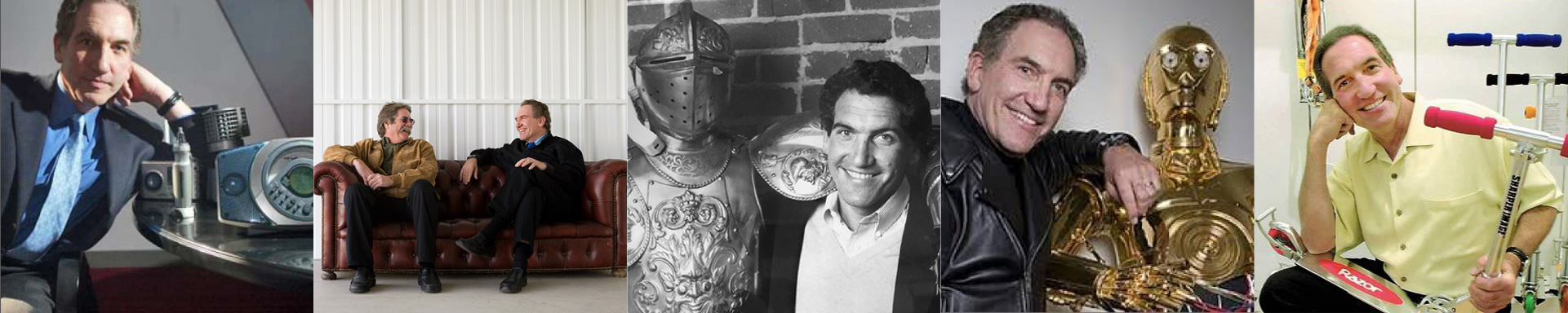

Back in 1984, his San Francisco-based Sharper Image was a fast-growing catalogue operation selling glitzy gadgets to professionals in their 30s and 40s who liked to flaunt their affluence. The company was well on its way to becoming a symbol of the greed-is-good, whoever-has-the-most-toys-when-he-dies-wins attitude of the 1980s.

“I can see the future,” Thalheimer boasted at the time. “I know when a trend is coming and when it’s leaving.”

These days–a couple of years after those go-go days got up and went, and on the heels of a steep decline in the company’s sales and its first annual loss–Thalheimer’s self-evaluation is a good bit harsher:

“I feel stupid. I should have realized that when all the Wall Streeters earning $300,000 a year were laid off, our business would suffer. . . . It was embarrassing to have a company with an image of the 1980s as we headed into the ‘90s.”

Indeed, the well-paid baby boomers who thrived on such frivolous excesses as $2,400 motorized surfboards and $1,800 home robots are now into environmentalism, home, family and practicality.

In short, they’ve grown up, and Sharper Image is scrambling to hone its image to adapt to the new ways. Would you believe organic flea relief for pets, an aluminum-can crusher and Birkenstock sandals?

“If you had told me five years ago that we’d be selling an organic flea product . . . ” Thalheimer said, shaking his head, at Sharper Image’s downtown San Francisco headquarters, decorated throughout in burgundy, mauve and gray.

Speaking in quiet, measured tones and sporting black Birkenstocks with his double-breasted suit and floral tie, Thalheimer, 43, began an interview with a series of mea culpas to help explain the company’s troubles. “For the last two to three years, I haven’t been a very good manager,” said Thalheimer, president, chairman and chief executive of Sharper Image.

He noted that, while he was distracted with remodeling a 100-year-old home in an old-money part of Marin County and caring for two young children, he managed to miss the shift toward hearth and Earth.

In the year ended Jan. 31, the company lost $2.3 million on $180.7 million in sales, which were down 13.4% from the previous year. One problem was that the company suffered from a too-rapid expansion to 75 stores. Ten were added in recessionary 1990, eroding catalogue sales, which Thalheimer said sank to $27 million from $50 million four years ago.

He’s scurrying to make up for the blunders. The May catalogue, for example, features on its cover and first two inside pages the Sjoberg Recyclor, a $99.95 gadget that will crush and store aluminum cans. A letter by Thalheimer emphasizes that the machine will run for two years on “the energy from recycling just one can.” Another full page is devoted to an Ultrasonic Pest Deterrent, designed to repel bugs and rodents without pesticides.

Thalheimer, who holds twice-monthly “green open houses” for inventors with ideas to peddle, is also quite proud of a $199.95 solar-powered watch that won’t add to “battery pollution” and a $129.95 Earth Bench, with slats made of recycled polyethylene milk containers and ornate sides fashioned from melted-down engine blocks.

Meanwhile, a dual-deck VCR for $995, the type of electronic gear on which much of Sharper Image’s early success was built, is relegated to Page 35.

Thalheimer said the company is vastly reducing its emphasis on costly brand-name electronics–on which Sharper Image ended up competing with too many discount chains and department stores–in favor of more reasonably priced, more practical products. However, Sharper Image continues to make room for an occasional “fantasy” item, such as a $14,000 rock-climbing simulator. Thalheimer, an avid athlete, founded Sharper Image in the late 1970s on proceeds from mail-order sales of a digital runner’s watch.

How quickly customers will begin to grasp the changes, and whether they will like them, is uncertain.

“Changing a company’s image is a very difficult and time-consuming thing to do,” said Maxwell Sroge, a catalogue consultant in Chicago. “The public tends to categorize certain companies in certain ways. Thalheimer did a good job of establishing the company as a source for yuppie toys.”

Michael Schachere, a psychologist in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, who treats the Sharper Image catalogue as “great bedroom reading,” said he has “always felt that they were catering too much to a yuppie image. Anyone who would buy anything from there would be a sucker.” Schachere said the shifts in merchandising strategy have largely escaped his attention.

At least one former competitor doubts that Sharper Image will have the resources to see the changes through over a long period.

“The business is not where it was in the 1980s,” said Larry Koenig, whose Price of His Toys closed its three Southern California stores in mid-1990 and whose catalogue is now in limbo under Chapter 11. “People just don’t want more things.”

Thalheimer has instituted some overdue cost cutting. The company has trimmed about 200 people from its 1,200-person payroll and closed two Bay Area distribution facilities to consolidate those operations in Little Rock, Ark., where Thalheimer grew up. Instead of mailing monthly catalogues, the company plans soon to switch to sending four or five per year.

Having ignored the company to his detriment, Thalheimer has become extremely hands-on, attending every trade show himself to nose around for new products. On a walk around the corporate office, he got into a long discussion with a catalogue art director over whether to include dolphin jewelry. At a meeting with a luggage vendor, he rejected as too pricey a $250 briefcase. This is definitely not the Sharper Image of old.

Thalheimer has by far the biggest stake in seeing the company’s fortunes brighten. Holder of 74% of the about 8 million shares, he has watched it–and his personal fortune–dive to about $2 a share from $10 when the company went public four years ago.

The stock closed unchanged Monday at $2.125 on the NASDAQ over-the-counter market.

Thalheimer contends that having all the money he did when the stock was higher made him nervous anyway.

“Being a fat cat is a very difficult position to be in,” he said. “It takes away your incentive. I much more enjoy having to prove something.”